Mario, the training ground for failures (wait...)

I’ve been playing video games ever since I can remember. Around the age I was born, video games began to make their emergence into the average American home, so it shouldn’t be a big surprise that I was cutting my teeth on games like Super Mario Brothers, Duck Hunt, and The Legend of Zelda. The NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) held my attention for as long as my parents would allow. Due to a lack of funds (I was a kid) and frugal parents, we didn’t have a very large collection of games, so if my brother and I wanted to play, we’d have to persevere through difficult stages and adapt to controls that were, at first, a major challenge. Over time, we developed skills and patience, trying new things and mastering levels and uncovering secrets that were hidden for only the best players to find. Our early failures and our motivation in spite of the struggles enabled us to enjoy to the utmost the games we played.

In stark contrast, a few years ago, my niece would want to play my Mario games, but would quickly succumb to quitting or playing the same early levels over and over again in order to not face the challenge of further stages. She would even resort to handing the controller off to me, so that I could get through the difficult areas. My niece was so bothered by the idea of failing that she was more likely to give up or not even enjoy the game by playing it. The challenge and the risk of struggle outweighed the desire to progress or gain some expertise that would ultimately lead to her satisfaction and freedom in playing the game.

How often is this like us, especially as artists and craftsmen (or even in other areas of our lives)? The art world and how we are received can be a very intimidating thing, for sure, but are we really helping ourselves when we are terrified of failure? This fear of failure is so ingrained within our society that it forces people into modes of operation that prevent personal growth and promote a kind of lowest common denominator approach to living. I think that most motivated people eventually move beyond this stage of their life at some point, but for many talented and intelligent people the fear is stronger than the will and ends up choking out their reason and hope.

In stark contrast, a few years ago, my niece would want to play my Mario games, but would quickly succumb to quitting or playing the same early levels over and over again in order to not face the challenge of further stages. She would even resort to handing the controller off to me, so that I could get through the difficult areas. My niece was so bothered by the idea of failing that she was more likely to give up or not even enjoy the game by playing it. The challenge and the risk of struggle outweighed the desire to progress or gain some expertise that would ultimately lead to her satisfaction and freedom in playing the game.

How often is this like us, especially as artists and craftsmen (or even in other areas of our lives)? The art world and how we are received can be a very intimidating thing, for sure, but are we really helping ourselves when we are terrified of failure? This fear of failure is so ingrained within our society that it forces people into modes of operation that prevent personal growth and promote a kind of lowest common denominator approach to living. I think that most motivated people eventually move beyond this stage of their life at some point, but for many talented and intelligent people the fear is stronger than the will and ends up choking out their reason and hope.

In fact, you can see it in schools. Most adolescents are afraid of ridicule to a certain degree (a form of “failure”) and end up stunting their growth as individuals and students in order to fit in with a certain crowd. They end up wearing masks and putting up shields so that their true selves will remain safe from the jabs and criticisms, while the outer facade is open to the blows. And the outer facade is much more capable of subverting any social destruction because it’s moldable and easy to change or ditch when the time calls for it. In my own life, I had a lot of growing to do in this area, as I found myself being different around different groups, in order that I would be accepted and praised.

Oh, high school, you're hallways are always so crowded

This may seem like it’s heading in the direction of “be your own unique little snowflake” territory, but that’s not where I’m trying to go. I’m more interested in subverting the notion that people shouldn’t fail. That failure is not an option. For sure, we aren’t hoping to fail. Shooting for failure isn’t commendable. However, knowing that we fail and accepting that we fail and learning from our failures instills upon us a confidence in the processes of life and growth.

I once heard a story of a professor who, during an assembly of students, declared that it was alright to fail. That many people fail in life at certain times and that it is through failure we can learn and become better. So, when a student fails an assignment, it gives that student time and motivation to reflect on why they failed and what they can do better next time. And that it is not the end of the world, but a step forward in their process of learning. This should give students hope that a failed class or a failed project will not stop them from getting better and even eventually producing great work. The students at the assembly were silent regarding this announcement, mostly due to the environment of the institute, which heralded results and success instead of learning. Another professor spoke up and declared that he, himself, had never failed a class and that he was proud of that accomplishment, because it proclaimed that he worked hard and was able to show what he was made of. The students applauded this announcement and fed the overwhelming ego of this professor.

So, it may come down to pride. Are we so proud that we are devastated by failures? Are we so proud that we can’t show when we are weak? If we look back at history’s greatest success stories and leaders, they aren’t filled with people who were afraid of failure. The greatest inventors built their lives around the notions of failure, submitting their minds and imaginations to the natural forces which ruled outside of their control. The social and national revolutions that brought great change and progress to the world were not held back by the idea of failure and, in fact, failed often. Abraham Lincoln is famously known for being a political failure for most of his career, yet he lives on in our history books as the greatest American president. Michael Jordan was cut from his high school basketball team, yet is now known as the greatest basketball player of all time. Albert Einstein could not speak fluently until he was nine years old and was expelled from school for being “slow”, yet he is now synonymous with genius. These are people who worked beyond their failures, using failure as a fuel for motivation and for strength, so that when the time for another challenge would come, they would then be prepared and ready to fight.

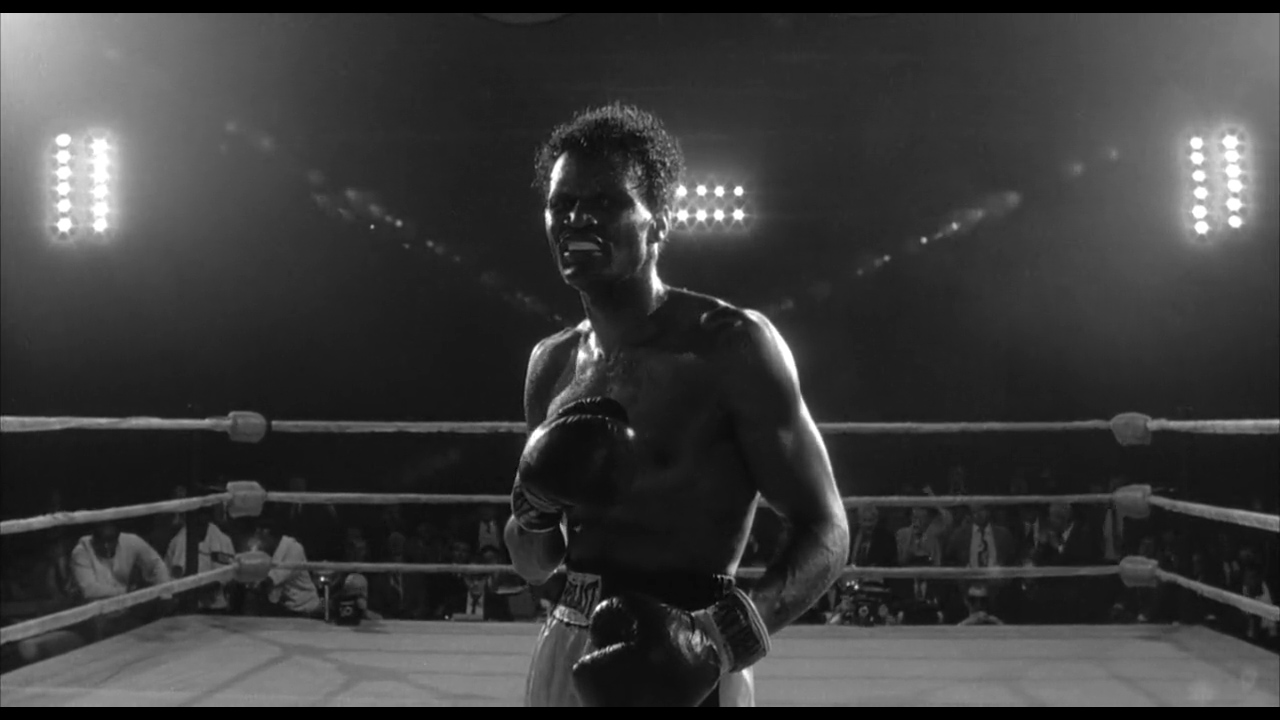

The Face of Failure

When failure happens, which it will, we can either be debilitated by it or treat it as a natural and common occurrence which will enable us to work past it, in order that we will not make the same mistakes again. There is no guarantee that we will have moved beyond whatever made us fall victim to failure, but there is the hope that we will learn from that failure and make the required changes, enabling us to grow and blossom.

In closing, I think humility is a much stronger antidote to the failures of life than pride. The person who fails while in a state of pride and glory, will take a much larger fall than the person who knows their humble status and works with confidence towards their goals. As they say, the bigger they are, the harder they fall. When we know we will fail at times, we are comfortable with moving forward afterwards, using what we have learned in the process. The hare was much more capable of winning the race, but fell into laziness because his confidence was derived from his pride in his abilities. He was not teachable. He thought that the whole race was no contest because he was so overqualified. Yet he lost. The tortoise, facing failure, still worked steadily, striving and moving, losing and losing and falling behind. In the end, the tortoise won. Not because of some intrinsic quality, but because in the face of failure, he moved forward. Meanwhile, the hare lost and couldn’t take the failure, because it pulled the rug out from underneath him. He went on to a life of heroin addiction. Or something. I may be confusing my tales here.

Look at the self-satisfied smugness. The tortoise has your number, man!

I’ll end with a nod towards Van Gogh, since this is an art blog and all, a man who is renowned as the cream of the crop of modern artists and the face of artistic genius. One of the most brilliant artistic minds in history was a huge failure. His paintings never sold, but for one to a relative. His style wasn’t respected. His life was lived in poverty and mental anguish. His dreams of being a missionary and evangelist, proclaiming the Gospel, were brought to an end when he was fired as a preacher. His life was, in all respects, failing. Constant failure. Yet most people don’t realize that he was always working on his art. His art wasn’t incredible from the get-go, like most everyone thinks. For sure, he had a tremendous ability, even early on (especially in the honesty of his work), but it was due to his endless studying and working that his art became so magnificent. As you struggle, as you debate with yourself, as you face failure, know that you’re not alone. In fact, you’re in good company.

"I've missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I've been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed." Michael Jordan

ClumpOfTreesWithVista1652LondonBM.jpg)