But perspective, as we understand it today, wasn't always in the bag of artist tricks. In the past, there was a more natural approach to it, observing relationships without adhering to a scientific application of measurement. This was an organic perspective, one which is readily observable in pre-Renaissance paintings. In many instances, artists still utilize the method of observing angles without implementing linear perspective techniques. Usually with smaller studies (still-life or figure, for instance) an artist may not need to employ linear perspective approaches.

What is linear perspective? It is a method discovered and utilized throughout the Renaissance by artists whose goal was to replicate more exactly how we see things within our picture plane. It is based within a geometric and mathematical system of measurements, which can give precise angles of objects. The simplest method of understanding linear perspective is to see "one-point perspective". Imagine a line of telephone poles traveling into the distance. Eventually they meet the horizon, at a certain point. You can trace a line from the top of the nearest telephone pole straight to the point on the horizon and, if each pole is of the same alignment and height of the nearest, you'll trace along the top of each pole. The same thing would happen if tracing from the bottom of the nearest pole straight to the point on the horizon. The following diagram (from Paul Heaston) shows how this works.

This can be used to highlight something important. For instance, Da Vinci uses one-point perspective to center The Last Supper on Jesus Christ, bringing all of the focus to the primary subject. You can see that he reinforces his perspective with a grid on the ceiling and divisions within the walls.

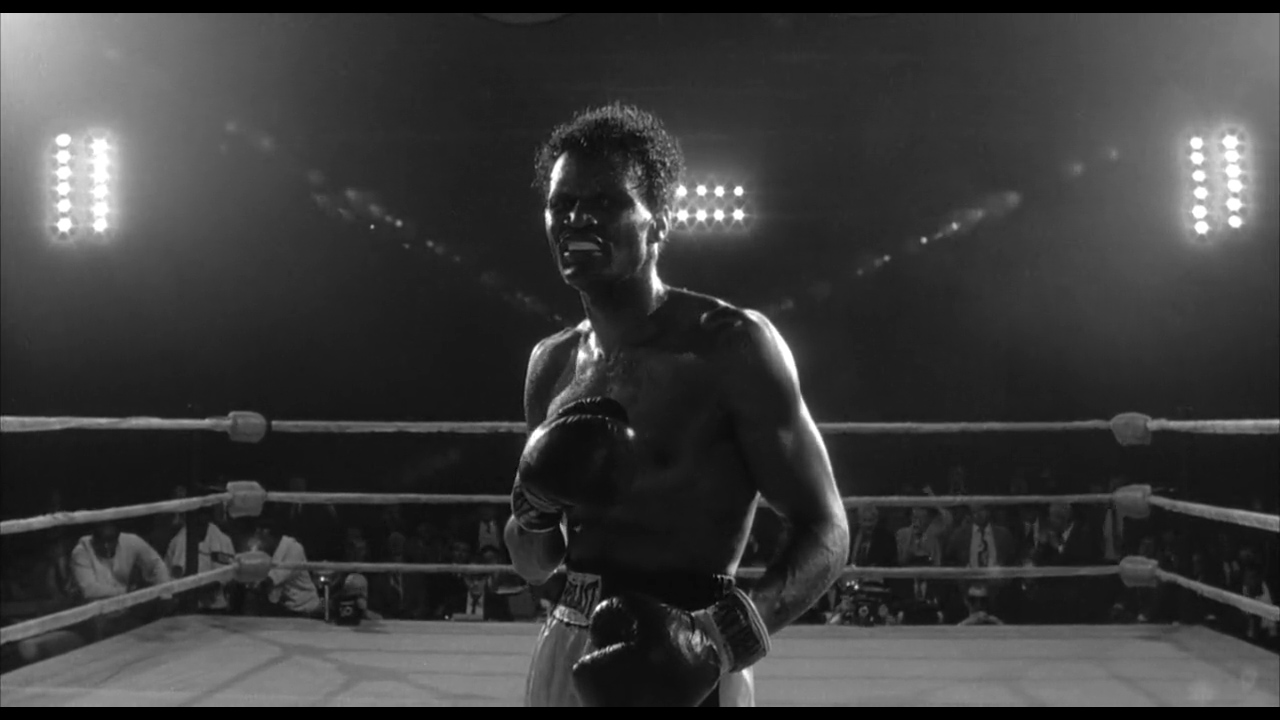

Scorsese uses this technique in Raging Bull to highlight the most crucial moment of Jake LaMotta's fight against Sugar Ray Robinson. All of the focus is on Sugar Ray. The whole arena seems to converge on him, and him alone. We are seeing him from the perspective of Jake and we see how powerful Sugar Ray is. We feel the importance of the moment.

Compare this to the storyboards for Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. We feel the character's confusion and tension. We are in the character's shoes. Each shot is full of overlapping objects and dynamic angles. This brings us right into the scene. We're not merely observing a character - we are the character!

These storyboards show us something called atmospheric perspective, as well. Observable in most of the thumbnails, but most noticeable in the image with the falling woman, we see that objects closer to our view have a higher value range than those further from our view. The man's hair is a dark black and the highlights on his face are a bright white, while the woman is simply varying degrees of grey. This occurs in real life. Let's imagine we are driving in a car. We see our dash, the land around us, and distant mountains. The shadows in the controls of our dash are going to be close to black, while the sunlight creates some high values on the brightest portions of our car. We are able to see a higher variety of values. If we look at the land around us, we will notice that the shadows aren't nearly as dark and the highlights are actually a bit lower in value than the ones that are nearest to us. And the distant mountains are essentially one value or maybe two, but there really is not much contrast.

Thickness of line can also illustrate perspective. Line, of course, is typically used in contour drawings. Contour drawings don't exactly lend themselves to differing value-tones in the same way that paintings do, so there are different methods of establishing perspective with only line.

So, as you can see there are many ways to approach perspective and it is a tough beast to wrangle. It is important for artists to practice it often, even when they think they know it all (which is never a good mindset for an artist).

"The divisions of Perspective are 3, as used in drawing; of these, the first includes the diminution (reduction) in size of opaque objects; the second treats of the diminution and loss of outline in such opaque objects; the third, of the diminution and loss of color at long distances." - Leonardo Da Vinci

ClumpOfTreesWithVista1652LondonBM.jpg)